April-May 2020 | Round Up

05 Jun 2020 |

|

We are faced with an unprecedented crisis which created a ‘new’ normal for all of us. Two things have remained unchanged: the suffering we cause animals and the compassion of the people who care about them. Our centre saw the intake of multiple animals and we’d like to salute and thank the frontline warriors for animals – the rescuers and volunteers who made sure injured animals and birds were taken care of.

Your support and encouragement helps them do what they are doing. You can continue to help us by donating here.

Below are some of the highlights of the past couple of months.

Leucistic Indian Cobra, January 2020

White cobra in a city neighbourhood

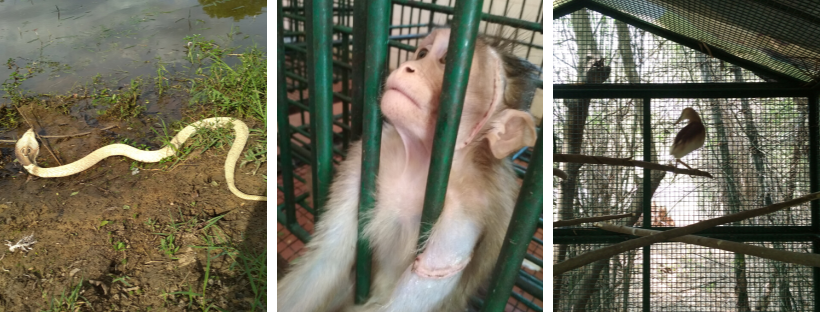

This unique white cobra was rescued after being spotted in Yelahanka (it was easy to spot). We found it had clear “spectacle” markings on its hood, as well as normal eye colour, which meant it was leucistic rather than a true albino. Leucistic and albino animals occur naturally, but are rare in the wild, partly because they cannot camouflage themselves like their normally-coloured companions.

This unique white cobra was rescued after being spotted in Yelahanka (it was easy to spot). We found it had clear “spectacle” markings on its hood, as well as normal eye colour, which meant it was leucistic rather than a true albino. Leucistic and albino animals occur naturally, but are rare in the wild, partly because they cannot camouflage themselves like their normally-coloured companions.

The 5-foot long adult snake had a wound on the tip of its tail. Its ribs were visible, indicating that it had not been getting enough to eat. We corrected that problem over the next 10 days, and it gained weight enthusiastically feeding on rats.

Though leucistic animals do have a harder time surviving in the wild, the very fact that the snake had reached its size meant that its survival skills were quite adequate. So we released it into a nearby forest pond and watched it swim away sedately to its new life.

Click Here to Donate to Help Us Help Them

Indian Peafowl, January 2020

Incarcerated in a farmhouse

These eight Indian peafowls were rescued from a farmhouse in Kumbarahalli, Hessarghatta, by Police Sub-Inspector Mr B Ravi, CID, Forest Cell. The peafowl were being reared along with domestic fowl, either for meat or feathers or both. The inhabitants of the farmhouse were booked under the Wildlife Protection Act. Peafowl is protected under Schedule I of the Act.

being reared along with domestic fowl, either for meat or feathers or both. The inhabitants of the farmhouse were booked under the Wildlife Protection Act. Peafowl is protected under Schedule I of the Act.

All eight were subadults, and we could not tell which were males and which were females, since the feathers that distinguish the sexes had not developed. They were healthy except for one oral infection, which we treated with antibiotics. As usual, we gave them medication to get rid of internal and external parasites.

We fed them an eclectic diet of insects, seeds, fruit and vegetables, to prepare them for the varied food choices available in the forest. When they came to us, they flew poorly and had no fear of people. This is often the case with wild animals rescued from captivity, and we have to reverse this conditioning so that they have a chance of survival when they leave us.

By April, they were rehabilitated. Their flight feathers had grown in and they were flying well. Best of all, they had become shy, avoiding us as much as they could. It is best not to handle these birds even during release. In their fright, they can struggle and damage their feathers, or worse develop the condition capture myopathy, which can cause fatal heart attacks even in healthy birds. So we released them by the simple expedient of leaving their enclosure door open. They wandered out, and are now roaming happily in the surrounding forests, visiting us once in a while to check on our condition.

Indian Pond Terrapins and Indian Flapshell Turtles, March 2020

Rehabilitated after life in a temple well

In early March, a temple in Malleshwaram who were cleaning their 50-foot-deep well brought up 7 Indian flapshell turtles and 11 Indian pond terrapins (along with a variety of fish). The temple authorities wisely decided to rehabilitate the terrapins and turtles rather than return them to the well, and hence they were brought to us. We weighed and inspected each one. Moss and algae were growing on their shells and a few had bite wounds on their limbs. The stress of overcrowding, coupled with the lack of direct sunlight, had evidently caused the larger turtles to bite their smaller brethren.

In early March, a temple in Malleshwaram who were cleaning their 50-foot-deep well brought up 7 Indian flapshell turtles and 11 Indian pond terrapins (along with a variety of fish). The temple authorities wisely decided to rehabilitate the terrapins and turtles rather than return them to the well, and hence they were brought to us. We weighed and inspected each one. Moss and algae were growing on their shells and a few had bite wounds on their limbs. The stress of overcrowding, coupled with the lack of direct sunlight, had evidently caused the larger turtles to bite their smaller brethren.

All were cleaned of algae and moss, and their wounds were dressed. They were placed in an enclosure with plenty of sunlight along with enough hiding places, should they become overwhelmed by their suddenly bright surroundings. Sadly, a few died from septicaemia resulting from their bite wounds. But most survived, and were released in batches into clean, unpolluted and undisturbed ponds inside a protected forest.

Click Here to Donate to Help Us Help Them

Indian Pond Heron, April 2020

Trapped in manja

This subadult Indian Pond Heron was found by one of our rescuers, entangled in manja (kite string) and hanging by its wings in Arekere. He would have died in a few hours from dehydration. Our intrepid rescuer immediately brought the bird down, and rushed him to our centre, braving the cops in the middle of the coronavirus lockdown. Luckily enough, the manja had not caused deep wounds on the bird’s wings. We gave him fluids for rehydration, and over the next week, painkillers and bandages. He was then shifted to the larger aviary for a flight check. His flight and appetite improved dramatically, and we released him in May beside a forest stream with plenty of fish. To our delight, he could barely wait to get out of his carrier and fly off into the nearby trees.

This subadult Indian Pond Heron was found by one of our rescuers, entangled in manja (kite string) and hanging by its wings in Arekere. He would have died in a few hours from dehydration. Our intrepid rescuer immediately brought the bird down, and rushed him to our centre, braving the cops in the middle of the coronavirus lockdown. Luckily enough, the manja had not caused deep wounds on the bird’s wings. We gave him fluids for rehydration, and over the next week, painkillers and bandages. He was then shifted to the larger aviary for a flight check. His flight and appetite improved dramatically, and we released him in May beside a forest stream with plenty of fish. To our delight, he could barely wait to get out of his carrier and fly off into the nearby trees.

Bonnet Macaque, May 2020

Victim of gang warfare

This subadult female bonnet macaque was found in Thalagatapura, Kanakapura, with severe open wounds on her head and forelimb, a victim of a vicious fight between two macaque troupes. We did emergency surgery and sutured her wounds under anaesthesia. She recovered very well, and within a week we could remove her sutures. We released her in late May where she had been found, so that she could reintegrate with her troupe and return to normal life.

This subadult female bonnet macaque was found in Thalagatapura, Kanakapura, with severe open wounds on her head and forelimb, a victim of a vicious fight between two macaque troupes. We did emergency surgery and sutured her wounds under anaesthesia. She recovered very well, and within a week we could remove her sutures. We released her in late May where she had been found, so that she could reintegrate with her troupe and return to normal life.